Did Machik Really Teach Chöd?

Did Machik Lapdrön Really Teach Chöd? A Survey of the Early Sourcesby Sarah Harding

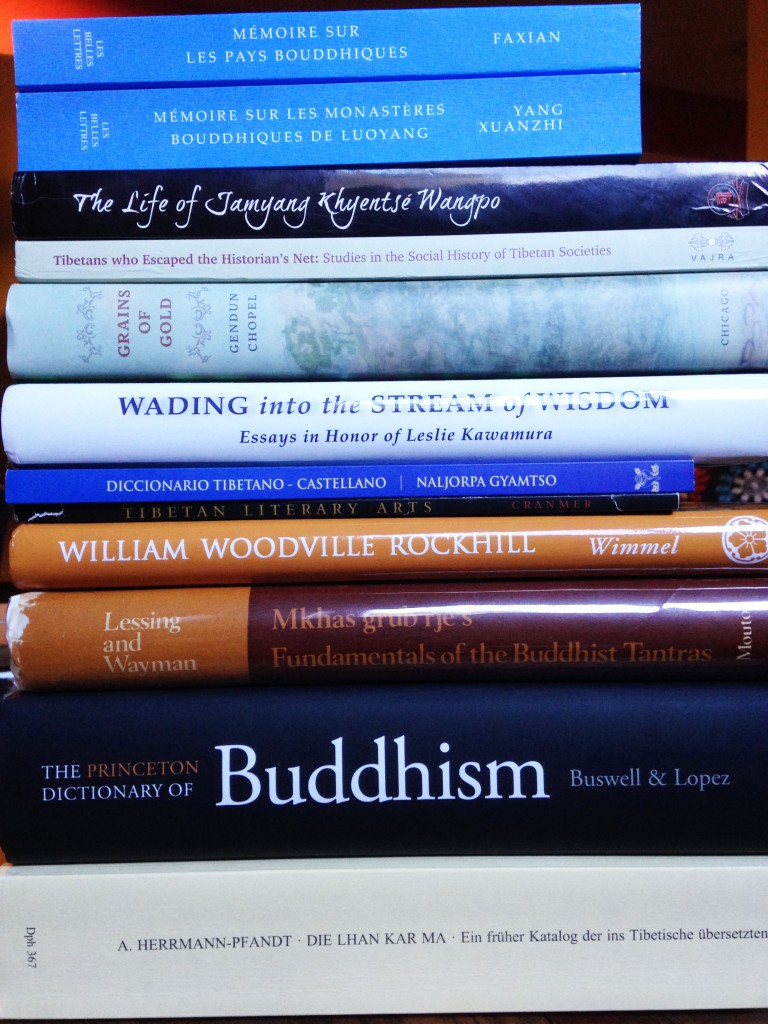

This provocative title is a result of a persistent question in the back of my mind for several years while I was researching and translating the early gcod texts from Jamgön Kongtrul’s Treasury of Precious Instructions (gDams ngag rin chen gter mdzod), the next ambitious project of the Tsadra Foundation. As I patiently went through the marvelous teachings in each text, I kept wondering when I would find the actual instructions on gCod (“chöd”), or “Severance,” that I was so familiar with from translating Machik’s Complete Explanation and from my own three-year retreat practice. The following is a short survey of these texts and my findings therein, which suggest that there is no clear attribution of the body-offering practice, and certainly not in the elaborate form that we find today.

gCod is primarily known, now quite famously, as a visualization practice in which one separates one’s consciousness from the physical body, and then turns around to cut up the remaining corpse and prepare it for distribution to gods, demons, and spirits of all kinds. The ritual offering may involve going to specific places where such spirits might be found, such as isolated, frightening, or haunted places. It is immediately obvious that several terrifying psychological experiences are invoked: fear of the unseen spirit world, of wilderness, and of the maiming and dismemberment of one’s body. It is thus widely recognized as a practice of “facing your fears” and overcoming them.

gCod was developed, also famously, by the woman Machik Lapdrön in the late eleventh century, during the time in Tibet when many other lineages were forming. Although technically gcod is known as a subsidiary of the zhi byed or Pacification teachings of Dampa Sangye, clearly Machik is the single mother of this baby. In the records of Machik’s brief encounters with Dampa Sangye, and in the only Indian gcod source text (gzhung) by Āryadeva the Brahmin, there is little about this specific practice. It therefore seems to be solely a result of Machik’s own realizations, and so is famous as an original Buddhist teaching indigenous to Tibet that uniquely spread to India in a reverse trajectory from all other doctrines.

The realization that gave birth to Machik’s gcod is said to have occurred during her recitation of a prājñāpāramitā text, which she regularly performed as part of her job as a household chaplain. Specifically, it was while reading “the chapter on māra.” Many suggestions have been offered as to which section that would be,

For examples of the possible lines that inspired Machik, see Harding, Machik’s Complete Explanation, pp. 35 and 97, and Zhi byed dang gcod yul gyi chos ‘byung rin po che’i phreng ba thar pa’i rgyan in gCod kyi chos skor, f. 2.

but in any case none of them throw light on the subject. The fact that it is mentioned at all, however, is very provocative. Māra, of course, is the antithesis of Buddha, and has been personified perhaps in the same way as enlightenment is personified as a buddha. Māra represents obstruction of the spiritual path or spiritual death (from Skt. mṛ-, “to die”) in all its forms. Besides the Buddha’s antagonist, a variety of māras were eventually classified into two sets of four, but there are many more examples in the texts I have translated here.[ref]Some examples from these texts are: the devil of belief in intrinsic existence, of merely mental emptiness, of making dharma a big project, of clinging to the reality of accomplishing enlightenment, of actual things, of depression and despair, of obstinate reification, etc.[/ref] It is tempting to imagine Machik’s inspiration as a profound encounter with the dark side, eventually resulting in the overcoming of that duality through the integration of the prājñāpāramitā teachings.

It should be noted that the translation of māra as bdud in Tibetan has further complicated the issue, given the hoards of bdud that roam Tibet. I have everywhere used “devil” or even “evil” for bdud, as distinguished from “demon” for ‘dre, although in Tibet the two are often interchangeable.

There is no shortage of reference to māras throughout the texts on gcod and their sources, and no question that the primary goal of these teachings is to deal with them, whether conceived of as demons or adverse circumstances or ego or as ultimate evil and ignorance. Simply put, the term used to describe that process is “chöd.” But it comes in two homonymic interchangeable spellings: gcod, which means “to cut” or “sever” and spyod, which means “behavior” or “action.” I have seen either used in alternate editions of the same text. Spyod and spyod yul instantly conjure up the bodhisattva’s conduct in the prājñāpāramitā literature, as in the recurring phrase: “In this way one should train in performing the activity of the profound perfection of wisdom.”

Quoted by Jamgön Kongtrul in The Treasury of Knowledge, Book Eight/Part Four: Esoteric Instructions, 276-77.

gCod as severance also has its Buddhist antecedents. The classic definition in gcod source material comes from Āryadeva’s Grand Poem, Esoteric Instructions on the Perfection of Wisdom:

Also called Grand Poem (Tshigs bcad chen mo) and Fifty Verse Poem (Tshigs su bcad pa lnga bcu pa), DNZ, vol. 14, p. 5. Other sources for the text are in the Narthang Tengyur, mdo, nyo, ff. 396b-399a; Golden Tengyur, nyo, ff. 517a-520a, and Kamnyön, History of Pacification and Severance, ff. 1-5.

Since it severs the root of mind itself,

and severs the five toxic emotions,

extremes of view, meditational formations,

conduct anxiety, and hopes and fears;

since it severs all inflation,

it is called “severance” by semantic explanation.

It is clear that the specific practice of cutting up the body is not alluded to in this definition, as well as all others that I encountered. In fact, it may just be an unfortunate parallel of usage that the process of resolution and integration of problems uses the same term as does the ordinary function of an axe or kitchen knife, or dragon glass, for that matter. We can think of the common term thag gcod pa (“decide, put an end to, determine, handle, deal with, treat”) to get more of a sense of this term, recalling also the interchangeability with spyod pa as “conduct and behavior.” What to do when things get tough? Act with determination.

Similarly, the term yul (“object”) in the longer name for this practice bdud kyi gcod yul (“the devil/evil that is the object to sever”) is used in the most abstract way and is attested in the Abidharma by Kongtrul and others. Consider the first verse in Machik Lapdrön’s source text, the bKa’ tshom chen mo (“Great Bundle”):

The root devilry is one’s own mind.

The devil lays hold through clinging and attachment

in the cognition of whatever objects appear.

Grasping mind as an object is corruption.

Or again, from the same text, referring to a more refined state of practice:

The conceit of a view free of elaboration,

the conceit of a meditation in equipoise,

the conceit of conduct without thoughts,

all conceits on the path of practice,

if engaged in as objects for even a moment,

obstruct the path and are the devil’s work.

The vast majority of the instructions in these early texts are on the practice and theory of prājñāpāramitā, as clearly indicated by their titles. These instructions are often reminiscent of mahāmudrā, and in fact later took on the epithet Severance Mahāmudrā (gcod yul phyag rgya chen po). For instance, from Machik’s Great Bundle:

Everything is self-occurring mind,

so a meditator does not meditate.

Whatever self-arising sensations occur,

rest serene, clear, and radiant.

lhan ne lhang nge lham me, alliterative words with variable experience-based meanings.

Even the earliest source text by Āryadeva the Brahmin employs such mahāmudrā signature phrases as “clear light,” (‘od gsal) and “mental non-engagement” (yid la mi byed pa),

‘Phags pa shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa’i man ngag, in gDam ngag mdzod (DNZ), vol. 14, p. 4.

while the commentary on those passages cites scripture such as Maitreya’s Highest Continuum

Mahāyānottaratantraśāstra. Theg pa chen po rgyud bla ma’i bstan bcos, cited inPure Honey: A Commentary on the Source Text of Severance, “Esoteric Instructions on the Perfection of Wisdom” by Kun dga’ dpal ‘byor, DNZ, vol. 14, p. 36 and elsewhere.

and other sources usually associated with the third turning. There is constant reiteration of this basic instruction to rest relaxed without doing anything. One of the more famous sayings attributed to Machik, often used as a reference to the gcod practice, is not particularly giving an instruction to sever and offer the body, but is more of a straightforward prājñāpāramitā or mahāmudrā instruction:

Rest the body in the way of a corpse.

Rest in the way of being ownerless.

Rest the mind in the way of the sky.

As a candle unmoved by the wind,

rest in the way of clarity with no thought.

As an ocean unmoved by the wind,

rest in a way serenely limpid.

hes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa’i man ngag yang tshom zhus len ma, DNZ, vol. 14, p. 107.

So where are the references to the practice of casting out the body as food that has made this practice so sensational? A quick survey of the ten early texts (two source texts plus Machik’s eight) making up 134 folia, turns up sixteen references to the catch phrase “separating the mind from the body,” all but one of which merely give mention to the term. This in itself, however, does not constitute the body-offering practice per se. Separating out the consciousness and “blending it with space” (byings rig bsre ba or ‘dre pa) or the much later nomenclature “opening the door to the sky” (nam mkha’ sgo byed) became signature gcod practices. Jamgön Kongtrul asserts that this is the main practice and relegates the body offering to post-meditation (rjes thob) or a branch (yan lag).

Treasury of Knowledge (Shes bya kun khyab) vol. 3, p. 426, and Garden of Delight, (Lus kyis mchod sbyin gyi zin bris mdor bsdus kun dga’i skyed tshal): “The main practice [of feeding the spirits] should be understood as an offshoot. But these days, most so-called severance practitioners don’t get the main root and only seem to desire the branches.” f. 11b.

The number of references to the actual body dismemberment is very rare, and, as I will suggest, limited to the texts of dubious origin. I will briefly survey the texts in the order they are found in the Treasury.

The verse text by Āryadeva the Brahmin, Esoteric Instructions on the Perfection of Wisdom, which is the only source text said to be of Indian origin, mentions the body offering only once, in the context of a classic graded path suitable for the three kinds of individuals:

Those with superior meditative experience

rest in the nondual meaning of it all.

The average practitioners focus on that and meditate.

The inferior offer their body aggregate as food.

The Great Bundle is taken as the earliest and most basic text attributed to Machik. As the story goes, she responded to three Indian inquisitors with an explanation of this composition and proved to them that that her teachings were indeed Buddha Word (hence bka’ in the title).

For this episode, see Harding, Machik’s Complete Explanation, p. 94.

It contains only one reference to a body offering:

Awareness carries the corpse of one’s body;

cast it out in an unattached way

in haunted grounds and other frightful places.

The third text classified as a source text by Jamgön Kongtrul is called Heart Essence of Profound Meaning.” That name came to indicate a whole cycle of teachings, but this source text is signed (not here, but in another edition) by Jamyang Gönpo (b. 1208?).

In gCod tshogs kyi lag len sogs, p. 101. The actual signature is “the Shakya monk, holder of the vajra, Prājñasambhava,” a translation of his ordination name Shes rab ‘byung gnas. His other works are signed “the Shakya monk, holder of the vajra, Mañjughoṣanatha, translating ‘Jam dbyangs dgon po.

In most records of the lineage, his name appears right after that of Machik’s son Gyalwa Döndrup, making him the earliest commentator on Machik’s teachings that I have yet encountered, nearly a century earlier than the third Karmapa (1284-1339), who is often given that credit. In this text, again, there is only one passage indicating the body-offering practice:

Free the mind of self-fixation by relinquishing the body aggregate as food.

Scatter the master of self-fixation by separating body and mind.

Liberate fear on its own ground by inspecting the fearful one.

Tossing away fixation on the body as self, obstacles will arise as glory.

We then come to an interesting text in the Treasury attributed to Machik called Precious Treasure Trove to Enhance the Original Source, A Hair’s Tip of Wisdom: A Source Text of Severance, Esoteric Instructions on the Perfection of Wisdom.

Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa’i man ngag gcod kyi gzhung shes rab skra rtse’i sa gzhung spel ba rin po che’i gter mdzod. DNZ, vol. 14, pp. 81-99.

It is evident that this is not a text by Machik, but a commentary on what may have been her teachings, which can be reconstructed by extracting the quoted segments. Using a methodology of searching citations in other gcod histories, specifically a huge auto commentary on the aforementioned Heart Essence by Jamyang Gönpo

sPyi ‘khrid chen mo, in gCod tshogs kyi lag len sogs, pp. 105-197. [/ref] and Jamgön Kongtrul’s Treasury of Knowledge,[ref]Shes bya kun khyab, vol. 3, pp. 420-28.

and Jamgön Kongtrul’s Treasury of Knowledge,

Shes bya kun khyab, vol. 3, pp. 420-28.

I have determined that when something called kha thor (“scattered”) is referenced, it is in fact the quoted segments of this text (with one exception that I could not find there). This was an exciting discovery and solved a long standing mystery, and also corroborated my analysis of this text as a commentary, although it doesn’t solve its authorship. That being said, however, there is not a single mention of casting out the body as food. The entire commentary, including the words apparently spoken by Machik, concern the perfection of wisdom.

Then there are two or three or more “bundles” attributed to Machik. Another Bundle (Yang tshom) is in verse form of a dialogue with her son Gyalwa Döndrup. The longer title is Another Bundle of Twenty-Five Instructions as Answers to Questions,

Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa’i man ngag yang tshom zhus len ma, DNZ vol. 14, pp. 101-115.

although not surprisingly there are actually twenty-eight questions in this version. Tacked on to that and unmentioned in any source or catalogue is a set of eighteen more questions with very cryptic verse answers, called Vajra Play (rDo rje rol pa). Then from an altogether different collection of ancient gcod texts

gCod tshogs kyi lag len sogs. TBRC W23390.

found at Limi monastery in Nepal, there is a text called, again, “Bundle of Precepts” (bKa’ tshom). The colophon titles it “Thirty-five Questions and Answers on the Bundle of Precepts, the Quintessence of the Mother’s Super Secret Heart-Mind.”

Ibid. p. 31: bKa’ tshoms kyi zhus lan sum bcu rtsa lnga pa/ a ma’i yang gsang thugs kyi nying khu.

While this text bears no resemblance to Machik’s Great Bundle of Precepts (bKa’ tshom chen mo), it is strikingly similar to Another Bundle. Of the thirty-five questions (and this time the number is correct!), twenty-six of them appear in Another Bundle. There is some suggestion in the colophon that this bundle may have been gathered by, again, Jamyang Gönpo. What all of this indicates to me is that there were more than one set of notes circulating as records of Machik’s dialogues, and that Jamgön Kongtrul ended up with this particular set for his Treasury, while his contemporary, Kamnyön Dharma Senge, apparently had access to another one, judging from the citations found in his Religious History of Pacification and Severance.

Khams smyon Dharma seng ge, also known as ‘Jig ‘bral chos kyi seng ge). The Religious History of Pacification and Severance: A Precious Garland Ornament of Liberation. Zhi byed dang gcod yul gyi chos ‘byung rin po che’i phreng ba thar pa’i rgyan. In Gcod kyi chos skor, pp. 411-597. Delhi: Tibet House, 1974.

To return to my point, there are but two brief mentions in Another Bundle concerning body offerings. The first is in a list of things to explain the term “unbearable” in response to the question “What is the meaning of “trampling upon the unbearable?” (mi phod brdzi ba), a phrase describing Severance. It says, “casting out the body to demons is unbearable (‘dre la lus skyur mi phod). The second instance is in response to the question “What should one do when sick?” and the answer is: “Chop up your body and offer it as feast.” (lus po gtubs la tshogs su ‘bul.[ref]DNZ vol. 14, p. 109.[/ref] Note the use of gtubs rather than gcod).

One last bundle is called The Essential Bundle (Nying tshom). Although it is attributed to Machik, it appears to be a summary of the other bundles, with a structural outline, scriptural citations, and even quotes from Machik, respectfully referred to as “Lady Mother” (ma jo mo). This assessment is further supported by the fact that it seems never to be cited in texts such as The Treasury of Knowledge, and is not mentioned in Kongtrul’s Record of Teachings Received,

Tashi Chöpel (bKra shis chos ‘phel), editor. Kong sprul gsan yig, or ‘Jam mgon kong sprul yon tan rgya mtshos dam pa’i chos rin po che mdo sngags rig gnas dang bcas pa ji ltar thos shing de dag gang las brgyud pa’i yi ge dgos ‘dod kun ‘byung nor bu’i bang mdzod. China: dPal spungs thub bstan chos ‘khor gling gi spar khang dam chos bang mdzod khang nas, Mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 2008.

nor in Kunga Namgyal’s short list of ten Indian dharmas.

In gCod kyi bshad pa gsal ba’i sgron me, p. 18 (f. 9b) It does include, however, bKa’ tshom and Yang tshom.

In any case, again there are only two references here: (1) if afraid: “Immediately hand over the body to those gods and demons without concern” and (2) “Those of inferior scope give over the body to the dangerous obstructers and rest in non-action within the state of mental non-recollection.”

hes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa’i man ngag bdud kyi gcod yul las nying tshom. DNZ, vol. 14, pp. 121 and 129.

Finally we have another set of three texts that I’ve called “Appendices” (Le lag), attributed to Machik. Here they are neatly divided into The Eight Common Appendices, The Eight Uncommon Appendices, and The Eight Special Appendices. However, in other supporting material when quotations are extracted from the “Appendices,” it is inevitably from the first set only, The Common Appendices. Moreover, in the aforementioned set of gcod texts from Limi monastery, there are just two sets of appendices, called “The Thirteen Appendices” and “The Eight Appendices.”

Le lag bcu gsum pa and Le lag brgyad pa in gCod tshogs kyi lag len sogs, pp. 45-66.

The latter corresponds loosely to the Eight Common Appendices in the Treasury. The Thirteen correspond neither to the Uncommon nor Special Appendices. I therefore only feel comfortable confirming the Common Appendices (of the three sets) as part of original teachings by Machik.

The Eight Common Appendices mention the body offering practice twice: once simply stating, “The body is a corpse, cast it out as food” (lus ni ro yin gzan du bskyur), and then again reiterating the threefold gradation of practice:

[Recite] “unspeakable, unthinkable, inexpressible,”

or else rest in the separation of body and awareness,

or else cast out the body as food

and rest within the state of evenness.

Thun mong gi le lag brgyad pa, DNZ, vol. 14, p. 139 (Appendix 7).

The Eight Uncommon Appendices is a very interesting text, albeit of doubtful origin. The eight sections are less arbitrary and present a progressive analysis of important elements in the practice. They are: (1) the meaning of the name, (2) the vital points, (3) practices applied to faculties, (4) clearing away obstructions, (5) deviations, (6) containing inattention (7) how to practice when sick, and (8) enhancement. The biggest surprise in this text is in the seventh appendix, which concerns various healing ceremonies, the nature of which is not found in any of the other texts, and involves such items as leper brains and widow’s underwear. However there is a basic principle here, that of dealing with the most difficult circumstances by facing them directly and employing a kind of “like heals like” practice. Thus substances normally considered unclean may be used to cure disease resulting from contamination. Or, as in modern homeopathy theory, the text offers a prescription to “pacify the heat of feverish illness in fire and resolve cold illness in water.”

nad thog tu nad dbab pa la/ nad tshad par ‘dug na/ tshad pa me nang du zhi bar bya ba dang/ nad grang bar ‘dug na skom thag chu nang du bcad pa’o. Thun mong ma yin pa’i le lag brgyad pa, DNZ, vol. 14, p. 148.

In some ways this could be taken as the essence of gcod practice, though it might be more difficult to identify Buddhist elements here. Of the five references to giving away the body, whether one’s own or the patient’s, two of them are in this section. For example: “To treat sriu,

Explained by Ringu Tulku, this refers to a kind of bad luck that occurs when a child dies and the propensity to die carries over to the next born. To remove this jinx (sriu), one has to do a ritual or ceremony using either the actual child or its clothing, and so forth.

take [the affected] to a haunted place and completely give over the flesh and blood to the harm doers. The mind will be blessed in emptiness.”

Ibid., pp. 149-50.

The last text of all those attributed to Machik Lapdrön is The Eight Special Appendices, and if the attribution is true, then this is where my theory falls apart. But of course I am somewhat skeptical. Stylistically it is very different from the ancient source texts, being comprised of eight sections outlining a progressive practice from beginning to end, much like a practice manual (khrid yig). The eight main headings are (1) the entry: going for refuge and arousing the aspiration, (2) the blessing: separating body and mind, (3) the meditation: without recollecting, mentally doing nothing, (4) the practice: casting out the body as food, (5) the view: not straying into the devils’ sphere of influence, (6) pacifying incidental obstacles of body and mind, (7) the sacred oaths of severance, and (8) the results of practice. The first four of these have further subcategories that contain not only descriptions, but also actual liturgy to be recited in the practice. And as the contents make clear, there is a whole section devoted to casting out the body as food, though not in the specific detail found in later works, such as Kongtrul’s Garden of Delight. In any case, this is the only text in the group where one can recognize the implementation of the practice of gcod as we have come to know it. And after the seemingly shamanic-type healing described in The Uncommon Appendices, it brings it all back into the Buddhist context with statements such as:

Casting out the body as food is the perfection of generosity, giving it away for the sake of sentient beings is morality, giving it away without hatred is patience, giving it away again and again is diligence, giving it away without distraction is meditative stability, and resting afterwards in the abiding nature of emptiness is the perfection of wisdom.

Khyad par gyi le lag brgyad, DNZ vol. 14, pp. 162-63.

The refuge visualization includes not only Machik herself but also her son Gyalwa Döndrup and grandson or grandnephew Tönyön Samdrup, which would seem to indicate that it is at least second if not third generation after Machik herself. More research needs to be done and hopefully more will come to light as I continue with the translations in the volumes on Severance and Pacification in The Treasury of Precious Instructions.

The question I proposed: “Is there enough material here to warrant attributing the body offering practice to Machik?” has led to much speculation. I would have to say that so far I have not seen much evidence linking Machik with the culinary detail of the spectacular charnel ground practices we call “Chöd.” Yet this is not much different than any investigation of the sources of a full-blown tradition. Did Virupa teach lam ‘bras? Did Niguma teach Six Yogas? The ḍākinī’s warm breath cools down and the trail is lost, leaving us chilling in a nice cool spot. Buddhist and non-Buddhist elements mix and mingle and we drink, hoping for a good brew to warm us.

Did Machik Lapdrön Really Teach Chöd? A Survey of the Early Sources

Presented by Sarah Harding at AAR 2013, Baltimore, MD

Attached here is a listing of early gcod texts from the gdams ngag mdzod – Sarah Harding

By Marcus Perman|April 28th, 2014|Categories: Fellows’ Writings, Presentations